Discussion of the security risks posed by climate change has become commonplace, and not for no reason: climate change acts as a “threat multiplier,” raising the risk of conflict by—among other things—threatening agriculture and access to water and making some parts of the world inhospitable to human life. Yet some people have pushed back on this framing of the issues, warning that framing climate change as a security issue invites us to think of people harmed by climate change not as victims, but as enemies. In a recent op-ed called “The Myth of Climate Wars?” Alaa Murabit and Luca Bücken argue that these critics are mistaken. “Rather than resisting the securitization of climate,” they say, “advocates and policymakers should be advancing…‘the climatization of security’” by “using security to increase the salience of climate action, highlighting the shortcomings of current security frameworks, and promoting gender inclusiveness and local leadership as holistic and long-term solutions for fostering local, regional, and international peace.”

There is compelling evidence that the resulting agreements are likely to be more durable and the peace longer-lasting if local women are more involved in conflict resolution and peacebuilding processes. Both for that reason and for the sake of gender equity more generally, Murabit and Bücken are quite right to suggest that we need to give them the tools they need to do that. Nevertheless, trying to temper discussions of the security threat posed by climate change by “climatizing” security talk seems to me a dangerous mistake. Rather than doing that, I submit, we should abandon the security frame entirely at the level of messaging, instead emphasizing conflict prevention and peacebuilding, terms that have the distinct advantage of not suggesting that desperate people whose wells have run dry are our enemies.

The only reason Murabit and Bücken give for retaining the emphasis on security is that “linking climate change to security can positively contribute to mobilizing climate action.” Presumably their thought is that talk of threats to our national security is likely to galvanize people into action by convincing them that climate change is a threat to their personal well-being. Certainly, that’s possible: if you’re worried about some threat, a rational response is to try to nip it in the bud by addressing its root cause. What seems more likely, however, is that many people will respond to discussions of the security threat climate change poses by pushing for hardened borders and more preparations for the climate wars they have been led to think they need to worry about. Consider, for instance, the reaction we have seen in the US to migrants from Northern Triangle countries seeking asylum, some of whom fled after finding that their traditional farming techniques no longer workable in light of increasing drought and changing rainfall patterns. Far from spurring climate action, first Candidate and then President Trump's and others' presentation of these people as threats to national security has spurred calls to “build the wall.” Similarly, refugees fleeing the Syrian Civil War--a conflict precipitated, in part, by record-setting droughts--have been greeted by nativist backlash throughout Europe.

Not only are there no good reasons to retain the security frame, however; framing climate change as a security threat carries serious risks. As Murabit and Bücken themselves note, emphasizing the security threat posed by climate change could “challenge already-strained international cooperation on climate governance, while driving investment away from necessary interventions—such as the shift to a low-carbon economy—toward advancing military preparedness.” Even more worrisome, there is a real chance that framing climate change as a security threat will exacerbate frightening recent trends in European and American politics. After all, the more people harmed by the disruptive effects of climate change are presented as threats to our way of life, the more reasonable it will come to seem to for governments to take extreme measures to protect their citizens. Just recently, for instance, the crowd at a Trump campaign rally cheered when an attendee suggested we shoot incoming migrants; President Trump made a joke about the comment.

Admittedly, Murabit and Bücken are probably right that, given its implications for migration, public health, resource scarcity, and other pressing policy issues, it will be difficult if not impossible to completely disentangle climate and security discussions. Moreover, and for the same reason, it is understandable that people have become concerned about potential security threats associated with climate change. Even so, I think we do well to at least de-emphasize the point if not avoid it entirely, emphasizing instead the need for cooperation and solidarity in the face of scarcity. What evidence we have available to us seems to suggest that emphasizing threats associated with these various phenomena does little to spur climate action; meanwhile, that strategy has the potential to do a good deal of additional harm to those most affected by climate change.

Reflections Here and There

Tuesday, May 28, 2019

Thursday, March 28, 2019

Three Steps Congress Can Take to Prepare for the Era of Mass American Climate Migration

Recently, and quite rightly, the potential for significant near-term increases in climate-induced migration has received a good deal of attention; however, relatively little discussion to date has focused on the potential for climate-induced displacement within the US. This is unfortunate, since some of the same climate impacts that will drive migration elsewhere are present here, including sea-level rise, increasing average temperatures, more frequent, longer, and more intense heatwaves, and wildfires. These climatic changes have the potential to displace millions of Americans: according to one study, sea-level rise alone may affect up to 13.1 million Americans by 2100, leading to “to US population movements of a magnitude similar to the twentieth century Great Migration of southern African-Americans.”[1] Migration on this scale would be extremely disruptive not just for migrants themselves but also for the communities where they take up residence. To minimize these harms, Congress should act now both to minimize the number of people who find themselves compelled to flee their homes and to help those forced to move. In what follows, I explores the various potential drivers of climate-induced displacement in the US and recommend policies to achieve both aims.

Potential Drivers of Climate-Induced Displacement in the US

The factors likeliest to lead Americans to move differ from one region to another.

On the east coast, by far the most potent driver of displacement is sea-level rise. In 2011, Hurricane Sandy demonstrated the extreme vulnerability of parts of New York, and Miami and Charleston are already experiencing considerable, frequent flooding. The latter have already driven some residents away.[2] Although communities across the east and gulf coasts are at risk, Florida appears to be by far the most vulnerable: a recent analysis by Climate Central found that twenty-two of the twenty-five US cities most at risk of coastal flooding are in the Sunshine State.[3]

In the Southwest, higher temperatures will be the primary driver of migration. Across the region, average and average maximum temperatures are expected to increase,[4] and heatwaves are projected to become more frequent, longer, and more intense.[5] For instance, in Phoenix—probably the most at-risk major city in the Southwest—the average temperature in July could approach 110 degrees Fahrenheit by 2100.[6] Heat stress is already the leading cause of weather-related death in the US, and the annual number of deaths is expected to increase as heatwaves worsen.[7] Faced with these scorching temperatures, we can expect that many people will pack their bags and head for cooler climes.

In the Western US as a whole, pressure to migrate will come, not from heat or drought

directly, but from their most destructive consequence: wildfires. According to a report by the US Global Climate Change Research Program, “[m]odels project…up to a 74% increase in burned area in California, with northern California potentially experiencing a doubling under a high emissions scenario toward the end of the century.”[8] Even worse, annual burn areas in western Colorado and northwestern Wyoming could increase by up to 650% with just one degree Celsius of additional warming—at this point, a fairly optimistic scenario (see Figure 1 at right).[9] Fires threaten the safety, not only of those in their direct path but, because of their effects on air quality, of those in surrounding areas as well.

Strategies for Decreasing the Risk of Displacement and Reducing Harms to Migrants

In light of these risks, Congress should take action to minimize the number of people who find themselves compelled to flee their homes and to reduce the harms suffered by those forced to move. Three strategies seem especially promising.

Strategy 1: Congress should create a new safety net program to help people adapt to climate change or move if necessary. As is the case with many environmental problems, sea-level rise, heatwaves, and wildfires will disproportionately affect lower-income people, who are at once less equipped to protect themselves from these threats and less capable of escaping them by migrating than wealthier people. A means-tested, federal safety net program allocating funds to lower income people to help them adapt—by, say, buying an air conditioner—or move away would help to reduce these inequalities. The program could be administered by FEMA, which already has the institutional infrastructure and expertise necessary to help people harmed by natural disasters. To make sure the people who need it most know about the program, Congress could allocate funds for TV advertising, as the Obama administration did to get the word out regarding the Affordable Care Act.

Strategy 2: Congress should mandate that prospective residents be informed of climate-related risks before buying property or building new homes. At present, many states require that sellers disclose flood-related risks, but twenty-one states require no such disclosure, and none require that wildfire- or heat-related risks be disclosed.[10] A program like this would help prospective residents to make informed decisions and to plan appropriately for future contingencies, likely reducing the number of people who move to disaster-prone areas in the first place. As a result, fewer people would be harmed, and the aforementioned safety net program would be cheaper.

Strategy 3: Congress should do what it can to promote of use zoning laws to limit or prohibit development in at-risk areas. Because zoning is typically handled at the local level, Congress’ power is limited here, but there are ways Congress can encourage local governments to enact smart zoning laws. For instance, Congress could make participation in the National Flood Insurance Program contingent on the enactment of strategic zoning laws. Like laws requiring disclosure to prospective residents of climate-related risks, laws like these would help to reduce the number of people living in disaster-prone areas, in turn reducing both the number of people who will be harmed and the cost of a new, climate-related safety net program.

All of these policies are likely to be opposed by homeowners in disaster-prone areas, who may very well see the value of their homes decrease as a result. This should not lead Congress to balk, for in the long run, these policies will help fall more people than they hurt. Still, the potential for resistance from homeowners might make it politically expedient to make the safety net program universal rather than means-tested. In that case, all homeowners would benefit from the program.

Conclusion

Climate change poses a variety of threats to the health and well-being of millions of Americans. Without aggressive mitigation measures in the very near future, many of the potential harms will be unavoidable. Even so, by working now to establish and publicize a new safety net program to help especially vulnerable people, mandating that prospective residents be fully informed of the risks, and taking what steps it can to encourage smart zoning laws, Congress can significantly reduce both the harms people will suffer and the extent to which climate change will upend their lives.

Notes

[1] Hauer et al., “Millions Projected to Be at Risk from Sea-level Rise in the Continental United States,” Nature Climate Change 6, no. 7 (2016): 691-695.

[2] Oliver Milman, “‘We’re Moving to Higher Ground’: America’s Era of Climate Mass Migration is Here,” The Guardian, September 24, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/sep/24/americas-era-of-climate-mass-migration-is-here (accessed 11/20/18).

[3] Kulp et al., “These U.S. Cities Are Most Vulnerable to Major Coastal Flooding and Sea Level Rise,” Climate Central, October 25, 2017, http://www.climatecentral.org/news/us-cities-most-vulnerable-major-coastal-flooding-sea-level-rise-21748 (accessed 11/20/18).

[4] Based on predictions from https://www.climate.gov/maps-data/data-snapshots/averagetemp-decade-LOCA-rcp85-2090-07-00?theme=Projections (access 11/20/18).

[5] Garfin, G., et al, “Ch. 20: Southwest,” in Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, ed. J. M. Melillo, Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and G. W. Yohe, U.S. Global Change Research Program (2014), p. 471. Available at https://nca2014.globalchange.gov/report/regions/southwest (accessed 11/20/18).

[6] Based on predictions from https://www.climate.gov/maps-data/data-snapshots/averagetemp-decade-LOCA-rcp85-2090-07-00?theme=Projections (access 11/20/18).

[7] Garfin, G., et al, “Ch. 20: Southwest,” p. 471.

[8] Garfin, G., et al, “Ch. 20: Southwest,” p. 468.

[9] National Research Council, Climate Stabilization Targets: Emissions, Concentrations, and Impacts over Decades to Millennia, (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2011), p. 180.

[10] Natural Resources Defense Council, “How States Stack Up on Flood Disclosure,” https://www.nrdc.org/flood-disclosure-map (accessed 11/27/18).

Potential Drivers of Climate-Induced Displacement in the US

The factors likeliest to lead Americans to move differ from one region to another.

On the east coast, by far the most potent driver of displacement is sea-level rise. In 2011, Hurricane Sandy demonstrated the extreme vulnerability of parts of New York, and Miami and Charleston are already experiencing considerable, frequent flooding. The latter have already driven some residents away.[2] Although communities across the east and gulf coasts are at risk, Florida appears to be by far the most vulnerable: a recent analysis by Climate Central found that twenty-two of the twenty-five US cities most at risk of coastal flooding are in the Sunshine State.[3]

In the Southwest, higher temperatures will be the primary driver of migration. Across the region, average and average maximum temperatures are expected to increase,[4] and heatwaves are projected to become more frequent, longer, and more intense.[5] For instance, in Phoenix—probably the most at-risk major city in the Southwest—the average temperature in July could approach 110 degrees Fahrenheit by 2100.[6] Heat stress is already the leading cause of weather-related death in the US, and the annual number of deaths is expected to increase as heatwaves worsen.[7] Faced with these scorching temperatures, we can expect that many people will pack their bags and head for cooler climes.

|

| Percent Increase in Median Annual Area Burned with a 1ºC Increase in Global Average Temperature. |

Strategies for Decreasing the Risk of Displacement and Reducing Harms to Migrants

In light of these risks, Congress should take action to minimize the number of people who find themselves compelled to flee their homes and to reduce the harms suffered by those forced to move. Three strategies seem especially promising.

Strategy 1: Congress should create a new safety net program to help people adapt to climate change or move if necessary. As is the case with many environmental problems, sea-level rise, heatwaves, and wildfires will disproportionately affect lower-income people, who are at once less equipped to protect themselves from these threats and less capable of escaping them by migrating than wealthier people. A means-tested, federal safety net program allocating funds to lower income people to help them adapt—by, say, buying an air conditioner—or move away would help to reduce these inequalities. The program could be administered by FEMA, which already has the institutional infrastructure and expertise necessary to help people harmed by natural disasters. To make sure the people who need it most know about the program, Congress could allocate funds for TV advertising, as the Obama administration did to get the word out regarding the Affordable Care Act.

Strategy 2: Congress should mandate that prospective residents be informed of climate-related risks before buying property or building new homes. At present, many states require that sellers disclose flood-related risks, but twenty-one states require no such disclosure, and none require that wildfire- or heat-related risks be disclosed.[10] A program like this would help prospective residents to make informed decisions and to plan appropriately for future contingencies, likely reducing the number of people who move to disaster-prone areas in the first place. As a result, fewer people would be harmed, and the aforementioned safety net program would be cheaper.

Strategy 3: Congress should do what it can to promote of use zoning laws to limit or prohibit development in at-risk areas. Because zoning is typically handled at the local level, Congress’ power is limited here, but there are ways Congress can encourage local governments to enact smart zoning laws. For instance, Congress could make participation in the National Flood Insurance Program contingent on the enactment of strategic zoning laws. Like laws requiring disclosure to prospective residents of climate-related risks, laws like these would help to reduce the number of people living in disaster-prone areas, in turn reducing both the number of people who will be harmed and the cost of a new, climate-related safety net program.

All of these policies are likely to be opposed by homeowners in disaster-prone areas, who may very well see the value of their homes decrease as a result. This should not lead Congress to balk, for in the long run, these policies will help fall more people than they hurt. Still, the potential for resistance from homeowners might make it politically expedient to make the safety net program universal rather than means-tested. In that case, all homeowners would benefit from the program.

Conclusion

Climate change poses a variety of threats to the health and well-being of millions of Americans. Without aggressive mitigation measures in the very near future, many of the potential harms will be unavoidable. Even so, by working now to establish and publicize a new safety net program to help especially vulnerable people, mandating that prospective residents be fully informed of the risks, and taking what steps it can to encourage smart zoning laws, Congress can significantly reduce both the harms people will suffer and the extent to which climate change will upend their lives.

Notes

[1] Hauer et al., “Millions Projected to Be at Risk from Sea-level Rise in the Continental United States,” Nature Climate Change 6, no. 7 (2016): 691-695.

[2] Oliver Milman, “‘We’re Moving to Higher Ground’: America’s Era of Climate Mass Migration is Here,” The Guardian, September 24, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/sep/24/americas-era-of-climate-mass-migration-is-here (accessed 11/20/18).

[3] Kulp et al., “These U.S. Cities Are Most Vulnerable to Major Coastal Flooding and Sea Level Rise,” Climate Central, October 25, 2017, http://www.climatecentral.org/news/us-cities-most-vulnerable-major-coastal-flooding-sea-level-rise-21748 (accessed 11/20/18).

[4] Based on predictions from https://www.climate.gov/maps-data/data-snapshots/averagetemp-decade-LOCA-rcp85-2090-07-00?theme=Projections (access 11/20/18).

[5] Garfin, G., et al, “Ch. 20: Southwest,” in Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, ed. J. M. Melillo, Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and G. W. Yohe, U.S. Global Change Research Program (2014), p. 471. Available at https://nca2014.globalchange.gov/report/regions/southwest (accessed 11/20/18).

[6] Based on predictions from https://www.climate.gov/maps-data/data-snapshots/averagetemp-decade-LOCA-rcp85-2090-07-00?theme=Projections (access 11/20/18).

[7] Garfin, G., et al, “Ch. 20: Southwest,” p. 471.

[8] Garfin, G., et al, “Ch. 20: Southwest,” p. 468.

[9] National Research Council, Climate Stabilization Targets: Emissions, Concentrations, and Impacts over Decades to Millennia, (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2011), p. 180.

[10] Natural Resources Defense Council, “How States Stack Up on Flood Disclosure,” https://www.nrdc.org/flood-disclosure-map (accessed 11/27/18).

Friday, October 6, 2017

Gun Control

I am a bit unusual among folks on the left insofar as I actually have a lot of personal experience with guns. Though I haven't done it since I was a teenager, I grew up hunting doves, squirrels, and deer with my grandpa; I think I killed my first deer when I was 11 or 12. That experience has led me to think a lot of things folks say about gun regulation is misguided. The push to outlaw assault weapons, for example, has long struck me as driven by an ignorant aversion to something that looks scary on the part of people who don't actually know anything about the relevant weapons. Generally speaking, so-called "assault weapons" are not different from semi-automatic weapons generally in ways that anyone should care about, at least as far as I know (happy to be corrected on this point). Other proposed measures, like outlawing high-capacity magazines, seem to me to go in the right direction but not nearly far enough.

For my part, I favor outlawing semi-automatic weapons, which make it much easier to kill more people in a given period of time and were used in both of the two worst mass shootings in the US in the last fifty years--in Orlando and Las Vegas.

So far as I can see, there is no good reason private citizens should be able to own these weapons. You certainly don't need them for hunting. If you need more than one shot to kill an animal, what you're doing is inhumane, and you should quit hunting, go to the range, and work on your shooting until you can hunt humanely. If the concern is self-defense, I fail to see why a shotgun used at close range isn't the most effective choice anyway. And if the idea is that we need guns so that we can form militias and, in that way, protect ourselves from government overreach--well, I think anyone who thinks that this is possible with semi-automatic weapons but not without is seriously underestimating the power of the US military. And besides, it seems to me clear that the public health benefits of a ban on semi-automatic weapons obviously outweigh whatever vanishingly small chance there is that a private militia with semi-automatic weapons would be more likely to succeed in its attempts to resist government overreach than one without. Honestly, the only reason I can think of to oppose such a ban is the irrational attachment to negative liberty that infects our public discourse generally.

However, there is good reason to go in for such a ban. There's robust evidence that regulations like this reduce gun-related deaths, and it's not hard to see why. Even if a ban didn't make it impossible to get hold of these, it would make doing so harder. It would accordingly keep many people from getting hold of these more lethal weapons, and that by itself would significantly reduce the number of deaths, even if mass shootings and other forms of gun violence still took place.

It's not clear whether or not banning these weapons would require revising the second amendment. (This piece, at least, suggests that it wouldn't.) If it would, though, I say so much the worse for the amendment.

For my part, I favor outlawing semi-automatic weapons, which make it much easier to kill more people in a given period of time and were used in both of the two worst mass shootings in the US in the last fifty years--in Orlando and Las Vegas.

So far as I can see, there is no good reason private citizens should be able to own these weapons. You certainly don't need them for hunting. If you need more than one shot to kill an animal, what you're doing is inhumane, and you should quit hunting, go to the range, and work on your shooting until you can hunt humanely. If the concern is self-defense, I fail to see why a shotgun used at close range isn't the most effective choice anyway. And if the idea is that we need guns so that we can form militias and, in that way, protect ourselves from government overreach--well, I think anyone who thinks that this is possible with semi-automatic weapons but not without is seriously underestimating the power of the US military. And besides, it seems to me clear that the public health benefits of a ban on semi-automatic weapons obviously outweigh whatever vanishingly small chance there is that a private militia with semi-automatic weapons would be more likely to succeed in its attempts to resist government overreach than one without. Honestly, the only reason I can think of to oppose such a ban is the irrational attachment to negative liberty that infects our public discourse generally.

However, there is good reason to go in for such a ban. There's robust evidence that regulations like this reduce gun-related deaths, and it's not hard to see why. Even if a ban didn't make it impossible to get hold of these, it would make doing so harder. It would accordingly keep many people from getting hold of these more lethal weapons, and that by itself would significantly reduce the number of deaths, even if mass shootings and other forms of gun violence still took place.

It's not clear whether or not banning these weapons would require revising the second amendment. (This piece, at least, suggests that it wouldn't.) If it would, though, I say so much the worse for the amendment.

Sunday, September 24, 2017

Some Very Rough Numbers on a Green New Deal

A couple

of recent developments got me thinking again about the possibility of a green

new deal.

The

first was the “Marshall

Plan for the United States” developed by the Center for American

Progress (CAP). Observing that wages are lower and unemployment is higher among

Americans without college degrees, they propose a jobs guarantee aimed at

putting these Americans back to work at well-paying jobs in education,

healthcare, and various forms of care work. For, they note,

There are not nearly enough home care workers

to aid the aged and disabled. Many working families with children under the age

of 5 need access to affordable child care. Schools need teachers’ aides, and

cities need EMTs.

They suggest, too,

that in addition to jobs, the government ought to fund infrastructure projects and apprenticeship programs

to train people for jobs for which they are not currently qualified.

The other was the

Democrats’ “Better Deal” initiative, which also

advocates job training and infrastructure investment.

All of this seems

great. A jobs guarantee empowers labor by reducing the power of the sack, and

because, on the CAP plan, these jobs would be relatively well-paid at $15/hour or

$36,000/year after Medicare and Social Security taxes, they would have the

welcome effect of putting upward pressure on wages throughout the economy. Moreover,

jobs like these that help us to sustain and improve our lives are precisely the

sorts of jobs we need more of as we seek to build a low-carbon economy.

The reason all this

got me thinking about a green new deal is that, their appeal notwithstanding, these

plans leave out a kind of work that is absolutely crucial to building a better

world: the construction and maintenance of green infrastructure, including not

just grid improvements and solar panel and wind turbine construction but also

the infrastructure necessary to expand opportunities for low-carbon leisure. Not

only is this work necessary; it is very well-suited for exactly the population

the CAP analysis is concerned with: you don’t need a college degree to do construction

work or to be a solar panel or wind turbine technician, though the latter do

require some training.

Maybe the reason for

this omission is that we can only fund so many jobs and so have to choose which

types of jobs to fund. But it is hardly obvious that green jobs are less

important than the kinds of jobs on which the CAP proposal focuses, and

besides, we may not have to choose: care work and educational jobs could be

funded from one source, green jobs from another. In particular, green jobs

might be funded using the revenue generated by a carbon tax and the $20.5 billion we currently spend every year subsidizing the

fossil fuel industry.

Senators Whitehouse

and Schatz recently proposed a carbon tax that would generate $2 trillion in

revenue over 10 years (details here), and

that proposal seems to be gaining some traction. Like many such proposals,

theirs is revenue-neutral, meaning that the revenue from this tax supplants

revenue that would otherwise have been collected by other means, such as the

corporate income tax. But a carbon tax needn’t be revenue-neutral. A carbon tax

might be structured in such a way that the revenue it generates does not

supplant but supplements other sources of revenue, and we might use that new

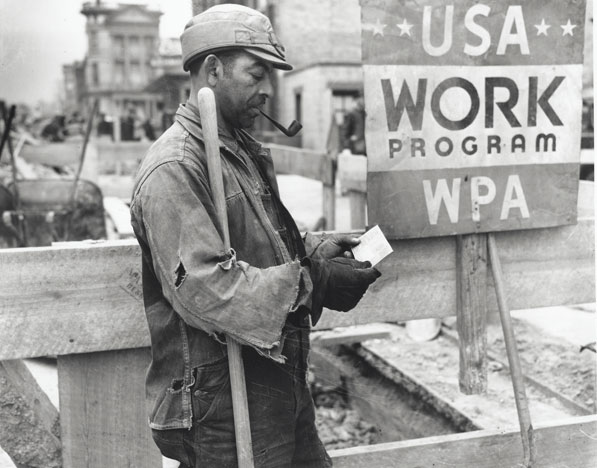

revenue to fund a WPA-style green jobs and

infrastructure program.

|

| A WPA worker receives a paycheck, January 1939. Source: National Archives. |

Now, as is

well-known, carbon taxes are regressive, so some of the revenue from the tax

would need to be used to offset price spikes for lower-income people.

Fortunately, this might be accomplished using only a small portion of the

revenue generated. Estimates as to how much of the revenue generated would be

necessary for this purpose appear to range from 10-25% (details here). Just to be safe,

we can be conservative in our estimates here and go with the highest estimates.

This would still leave 75% of the annual proceeds for other things.

Now it is worth

saying that even this number may be too high. We might also want to reserve

some of the revenue collected via a carbon tax to seed a rainy day fund for

Americans forced to relocate as a result of climate change and for others

adversely affected thereby. But even if we used another 25% of the revenue

collected for that purpose, we would still collect about $100 billion per year

for 10 years. Using the numbers in the CAP proposal as a guide, that should be

enough to fund about 2.8 million jobs at an after-tax wage of $15/hr. Were we

to also use the $20.5 billion/year we currently spend in fossil fuel subsidies

for this purpose, we could create about 570,000 more such jobs, making for a

total of 3.37 million jobs. And

remember, that’s using the most conservative figures around to make sure that

tax isn’t regressive and using an enormous amount of money to help people

adversely affected by climate change.

This is, of course,

a highly ambitious proposal, one unlikely to get anywhere in the current

political climate. Nevertheless it deserves serious consideration for several

reasons. Not only is it exactly the kind of bold vision needed to correct the impression that the Democratic

Party doesn’t stand for anything. Not only does it have the same advantages as

the CAP proposal with respect to the empowerment of labor and economy-wide

upward pressure on wages. In addition to all this, it has a distinct advantage

over many other carbon tax proposals. Even if this is not exactly the aim, the

likely if not inevitable effect of instituting a carbon tax high enough to

ensure that the prices of fossil fuels reflect their true cost to society is to

end our reliance on such fuels. It is for that reason a bad idea to use the

revenues generated thereby to fund anything we expect to continue to need funds

after we are no longer using carbon-intensive fuels: otherwise, we set

ourselves up for funding shortfalls in the future. The advantage of using

revenues from a carbon tax to fund a WPA-style green jobs program is that many

such jobs will become unnecessary around the same time we stop using fossil

fuels, and not just coincidentally. For these are precisely the jobs that bring

into existence the infrastructure we need in order to wean ourselves off of

gas, oil, and coal. As soon as they’re done, there will be nothing left to tax.

Notably, this aspect

of the proposal also gives to it something of a poetic character: for the

proposal is, in effect, to build the new world on the back of the old.

Thursday, March 2, 2017

In Defense of Safety Nets

With the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and much of the rest of America's already-inadequate safety net on the chopping block, it seemed to me fitting to write a short defense of safety nets, one that emphasizes the moral and philosophical position underlying my view here rather than getting lost in the weeds, as so many discussions of safety net programs seem to.

My view here is grounded in the one of the oldest and most widely accepted moral views, the so-called Golden Rule: we ought to do to others as we would prefer that they do to us were our circumstances relevantly similar to theirs. It is also grounded in the view that one of the government's most basic functions is to protect its citizens from danger, one form of which is the vicissitudes of fortune (illness, unexpected expenses, damage to or loss of property, etc.). Both these thoughts are captured nicely by the following thought experiment, developed by the American political philosopher John Rawls in the early '70s.

Try to imagine that you are in a situation where you don't know anything about what kind of person you are and are trying to imagine what a country should be like. So: you don't know if you're a man or a woman; what color your skin is; if you're able-bodied; if you're Christian, Muslim, non-religious, Jewish, or something else; if you're gay, bisexual,or straight; if you're cis- or transgender; if you're poor or rich or somewhere in between; if you have a family and friends you can rely or in hard times or if you don't; and so on. In short, all you know is that you live in some country. Now consider: if that were your situation, and if you could decide what the country you lived in would be like, how would you want it to be?

I don't think that's right or fair; in my view a society cannot call itself decent if it is willing to take the chance that people it might have helped die on the street. I accordingly think the government should be willing to extend a hand to anyone who needs it--to give them food to eat, a roof over their heads, and clothes to wear, whatever their color, creed, sexual orientation, etc. That way, even if I don't know anything about myself other than that I'm a citizen or perhaps even just a resident, I know that, if I'm in trouble, I can count on someone offering it to me, whatever else might turn out to be true about me. I don't just have to hope that someone might have decided to start a charity or a church that will be willing to help me: I can count on it.

The fundamental point underlying all this is a simple moral one. The vicissitudes of fortune are a kind of danger that haunts even those of us who manage to escape its cruelest blows. And sometimes, when disaster does strike, people end up in situations with which they can't or don't know how to cope--often through no fault of their own. In those moments people need a helping hand. Being a decent society means recognizing this and doing what we can to help those who fall on hard times, not turning our backs on the needy to punish the takers, all the while singing paeans to liberty and caught up in absurd, Randian fever dreams about self-made men. The hard truth is that none of us knows when we might need a hand; decency demands that we be willing to offer ours.

My view here is grounded in the one of the oldest and most widely accepted moral views, the so-called Golden Rule: we ought to do to others as we would prefer that they do to us were our circumstances relevantly similar to theirs. It is also grounded in the view that one of the government's most basic functions is to protect its citizens from danger, one form of which is the vicissitudes of fortune (illness, unexpected expenses, damage to or loss of property, etc.). Both these thoughts are captured nicely by the following thought experiment, developed by the American political philosopher John Rawls in the early '70s.

Try to imagine that you are in a situation where you don't know anything about what kind of person you are and are trying to imagine what a country should be like. So: you don't know if you're a man or a woman; what color your skin is; if you're able-bodied; if you're Christian, Muslim, non-religious, Jewish, or something else; if you're gay, bisexual,or straight; if you're cis- or transgender; if you're poor or rich or somewhere in between; if you have a family and friends you can rely or in hard times or if you don't; and so on. In short, all you know is that you live in some country. Now consider: if that were your situation, and if you could decide what the country you lived in would be like, how would you want it to be?

In particular, what kinds of resources would you like to have available to you if you fell on hard times? For example, would you want it to be the case that, if you needed help, the only place to turn would be the church and charities? Remember: because these are private organizations run by private citizens, there is no guarantee there will be any of them at all and, if there are, no guarantee that there will be enough of them or that they will be able to provide the help you need. Moreover, even if there are enough and they can help, they might not. Maybe you're gay and they don't like gay people. Maybe you're black and they don't like black folks. Maybe you're Jewish and they don't like Jews. And so on.

I don't think that's right or fair; in my view a society cannot call itself decent if it is willing to take the chance that people it might have helped die on the street. I accordingly think the government should be willing to extend a hand to anyone who needs it--to give them food to eat, a roof over their heads, and clothes to wear, whatever their color, creed, sexual orientation, etc. That way, even if I don't know anything about myself other than that I'm a citizen or perhaps even just a resident, I know that, if I'm in trouble, I can count on someone offering it to me, whatever else might turn out to be true about me. I don't just have to hope that someone might have decided to start a charity or a church that will be willing to help me: I can count on it.

A lot people have concerns about the kinds of government programs I'm advocating, and it would be impossible to address all of them without making this far too long. So I just want touch at least briefly on those I hear most often.

Perhaps the concern about safety net programs I hear expressed most frequently is that they enable free riders or moochers by giving them something for nothing. I think the fundamental thought behind this objection is that our society should be such that, the harder a person works and the higher the quality of their work, the better they do. Safety nets irritate people who press this objection because, they think, they stand in the way of the realization of this ideal by rewarding laziness. This strikes them as unfair to people who are willing to do their part.

In principle, I

don't see anything wrong with this meritocratic ideal. In general, it seems to

me a good thing to reward people for working hard at helpful tasks. Nevertheless I think this is a very bad objection to safety nets for a couple of reasons.

First, I just do not think our society is anywhere close to being meritocratic in this sense. On the one hand, people born into rich or powerful families often do quite well for themselves despite not being especially capable. Sometimes this is because their families have connections and influence that enable them to do things they wouldn't otherwise be able to; for example, this appear to be what explains the admission to Harvard of Jared Kushner, Donald Trump's son-in-law and according to his high-school teachers a "less than stellar" student (details here). Other times it is just because such people come into the world with a kind of support system or fail-safe people born into less fortunate circumstances do not: if they ever end up in a tight spot, they can rely on their family's wealth and connections to get them out of it. On the other, our society often throws up arbitrary barriers to advancement that make it much harder for some people to do well for themselves in the first place. These obstacles often take the form of class-, race-, gender-, sexual orientation-, or gender identity-based prejudice and structural barriers. I support safety nets in part because I think they go some way toward rectifying that defect by removing these arbitrary obstacles to advancement by making available to everyone the kind of support system only the rich would otherwise have.

But--second--even if our society were perfectly meritocratic--even if everybody's level of well-being were perfectly correlated with how talented or capable they are and how hard they are willing to work--we would still need a robust safety net. For the mere fact that someone is not particularly capable or useful should not mean that they lose their house, that they die because they can't afford healthcare, or that they go hungry. We should not punish those with mental illness or with physical or mental disabilities for being the way they are; instead, recognizing our common humanity and the vulnerability that is a basic fact of all our lives, we should take care of them. The opposite view is just callous indifference.

Someone might grant me all this but still worry that people who don't really need them will take advantage of these programs. Again I agree that it is a bad thing for people to be lazy and take advantage of programs intended to help people get back on their feet: the public coffers are not bottomless, so we would do well not to waste money on people who don't really need it. But this belief leads me to different conclusions than it does those who press this objection because I care more about ensuring that people do not go hungry, end up homeless, lose limbs from untreated diabetes, etc. than I do about the possibility that someone might take advantage of safety net programs. For this reason, my response to learning that people are taking advantage of safety net programs is to think that, if anything, we need to alter the programs they’re taking advantage of to make it harder and less appealing for them to do that, not abolish the programs. But even this, it bears saying, is a dangerous path. For once we start down it, there is a tendency to increase the number of hoops people have to jump through in order to benefit from the program in question. Not only does this increase the likelihood that people who need those benefits won't get them--a possibility that, to my mind, is far worse than some getting them even though they don't need them--it also often increases the cost of the program. That in turn may decrease public support for it and lead, in time, to its elimination. So there are sometimes significant costs to implementing measures designed to restrict access to safety net programs, dangers anyone attempting to eliminate free riders would do well to keep in mind. Though not ideal, it is far better for someone to get a benefit they don't need than for them to need a benefit they can't get.

Another common objection to safety net programs is that, although it is certainly a good thing to feed the hungry, house the homeless, tend the sick, and so on, the associated costs to our liberty far outweigh the benefits of governmental programs designed to do this. This is the objection to the ACA I've heard more often than any other: people hate being coerced into buying healthcare. Against this, however, two points. First, liberty is without a doubt a valuable thing, but this objection suggests a perverse fetishization of liberty, a blind zeal for non-interference that fails to distinguish those freedoms that are worth caring about from those that are not. For supposing that we are talking about offering these programs in a relatively wealthy society and financing them primarily by taxing its wealthiest citizens--as we undeniably are in the United States--the freedom in question is that of people who have more than they need to hoard their wealth and deny to those who lack it the minimum necessary for a decent life. I cannot see a society that values that particularly liberty over meeting people's basic needs as anything but cruel and selfish. Moreover, it must be said that that safety net programs that ensure that all people have access to housing, enough food and clothing, and healthcare are themselves in an important sense liberating: by putting in place a kind of ground floor below which people are not allowed to fall, they insulate people from the whims of fate and, in that way, go some way toward liberating them from oppressive forces to which all of us are subject to at least some extent.

First, I just do not think our society is anywhere close to being meritocratic in this sense. On the one hand, people born into rich or powerful families often do quite well for themselves despite not being especially capable. Sometimes this is because their families have connections and influence that enable them to do things they wouldn't otherwise be able to; for example, this appear to be what explains the admission to Harvard of Jared Kushner, Donald Trump's son-in-law and according to his high-school teachers a "less than stellar" student (details here). Other times it is just because such people come into the world with a kind of support system or fail-safe people born into less fortunate circumstances do not: if they ever end up in a tight spot, they can rely on their family's wealth and connections to get them out of it. On the other, our society often throws up arbitrary barriers to advancement that make it much harder for some people to do well for themselves in the first place. These obstacles often take the form of class-, race-, gender-, sexual orientation-, or gender identity-based prejudice and structural barriers. I support safety nets in part because I think they go some way toward rectifying that defect by removing these arbitrary obstacles to advancement by making available to everyone the kind of support system only the rich would otherwise have.

But--second--even if our society were perfectly meritocratic--even if everybody's level of well-being were perfectly correlated with how talented or capable they are and how hard they are willing to work--we would still need a robust safety net. For the mere fact that someone is not particularly capable or useful should not mean that they lose their house, that they die because they can't afford healthcare, or that they go hungry. We should not punish those with mental illness or with physical or mental disabilities for being the way they are; instead, recognizing our common humanity and the vulnerability that is a basic fact of all our lives, we should take care of them. The opposite view is just callous indifference.

Someone might grant me all this but still worry that people who don't really need them will take advantage of these programs. Again I agree that it is a bad thing for people to be lazy and take advantage of programs intended to help people get back on their feet: the public coffers are not bottomless, so we would do well not to waste money on people who don't really need it. But this belief leads me to different conclusions than it does those who press this objection because I care more about ensuring that people do not go hungry, end up homeless, lose limbs from untreated diabetes, etc. than I do about the possibility that someone might take advantage of safety net programs. For this reason, my response to learning that people are taking advantage of safety net programs is to think that, if anything, we need to alter the programs they’re taking advantage of to make it harder and less appealing for them to do that, not abolish the programs. But even this, it bears saying, is a dangerous path. For once we start down it, there is a tendency to increase the number of hoops people have to jump through in order to benefit from the program in question. Not only does this increase the likelihood that people who need those benefits won't get them--a possibility that, to my mind, is far worse than some getting them even though they don't need them--it also often increases the cost of the program. That in turn may decrease public support for it and lead, in time, to its elimination. So there are sometimes significant costs to implementing measures designed to restrict access to safety net programs, dangers anyone attempting to eliminate free riders would do well to keep in mind. Though not ideal, it is far better for someone to get a benefit they don't need than for them to need a benefit they can't get.

Another common objection to safety net programs is that, although it is certainly a good thing to feed the hungry, house the homeless, tend the sick, and so on, the associated costs to our liberty far outweigh the benefits of governmental programs designed to do this. This is the objection to the ACA I've heard more often than any other: people hate being coerced into buying healthcare. Against this, however, two points. First, liberty is without a doubt a valuable thing, but this objection suggests a perverse fetishization of liberty, a blind zeal for non-interference that fails to distinguish those freedoms that are worth caring about from those that are not. For supposing that we are talking about offering these programs in a relatively wealthy society and financing them primarily by taxing its wealthiest citizens--as we undeniably are in the United States--the freedom in question is that of people who have more than they need to hoard their wealth and deny to those who lack it the minimum necessary for a decent life. I cannot see a society that values that particularly liberty over meeting people's basic needs as anything but cruel and selfish. Moreover, it must be said that that safety net programs that ensure that all people have access to housing, enough food and clothing, and healthcare are themselves in an important sense liberating: by putting in place a kind of ground floor below which people are not allowed to fall, they insulate people from the whims of fate and, in that way, go some way toward liberating them from oppressive forces to which all of us are subject to at least some extent.

The fundamental point underlying all this is a simple moral one. The vicissitudes of fortune are a kind of danger that haunts even those of us who manage to escape its cruelest blows. And sometimes, when disaster does strike, people end up in situations with which they can't or don't know how to cope--often through no fault of their own. In those moments people need a helping hand. Being a decent society means recognizing this and doing what we can to help those who fall on hard times, not turning our backs on the needy to punish the takers, all the while singing paeans to liberty and caught up in absurd, Randian fever dreams about self-made men. The hard truth is that none of us knows when we might need a hand; decency demands that we be willing to offer ours.

Wednesday, June 15, 2016

Banning Muslims and Regulating Guns

Many people oppose stricter gun regulations because, they say, regulation will not stop malicious actors from getting guns (as prohibition did not stop people from obtaining alcohol). Many of the same people, I assume, support Trump’s plan to ban Muslims from entering the country. Question: why not think Trump’s plan is problematic in the same way? If the thought is that government regulations are too blunt an instrument to solve the problems in the one case, why not in the other? Is it so hard to imagine that jihadis could find ways around a ban on Muslims entering the country?

The answer cannot be that while such a ban would surely not stop everyone we don’t want here from getting into the country, it would stop some, since proponents of gun regulation can take the same line: while regulations will not completely stop malicious actors from obtaining weapons, they will stop some, and so they’ll make us safer overall. For consistency’s sake, we should take the same line in both cases.

Admittedly, the argument cuts both ways: supporters of Trump’s plan might criticize those proponents of gun regulation who oppose it on the grounds that they are opposing a plan that would make us safer overall (even if it wouldn’t eliminate terrorist attacks entirely). (Whether or not such a ban would in fact make us safer is less clear in this case--not least because it would not be surprising if implementing a ban like this were to fan the flames of radicalism--but I won’t worry about this.) The answer for proponents of gun regulation seems straightforward here: even if it would make us safer, such a ban would be incompatible with some of our deepest values, tolerance of religious and other forms of diversity and opposition to arbitrary discrimination.

Opponents of regulation might of course reply that, again, the argument cuts both ways, since regulation violates their right to bear arms. But it is hardly clear that citizens have a right to relatively unrestricted access to lethal weapons; at the very least, that claim seems much harder to defend than does tolerance of harmless forms of diversity and opposition to arbitrary discrimination.

The answer cannot be that while such a ban would surely not stop everyone we don’t want here from getting into the country, it would stop some, since proponents of gun regulation can take the same line: while regulations will not completely stop malicious actors from obtaining weapons, they will stop some, and so they’ll make us safer overall. For consistency’s sake, we should take the same line in both cases.

Admittedly, the argument cuts both ways: supporters of Trump’s plan might criticize those proponents of gun regulation who oppose it on the grounds that they are opposing a plan that would make us safer overall (even if it wouldn’t eliminate terrorist attacks entirely). (Whether or not such a ban would in fact make us safer is less clear in this case--not least because it would not be surprising if implementing a ban like this were to fan the flames of radicalism--but I won’t worry about this.) The answer for proponents of gun regulation seems straightforward here: even if it would make us safer, such a ban would be incompatible with some of our deepest values, tolerance of religious and other forms of diversity and opposition to arbitrary discrimination.

Opponents of regulation might of course reply that, again, the argument cuts both ways, since regulation violates their right to bear arms. But it is hardly clear that citizens have a right to relatively unrestricted access to lethal weapons; at the very least, that claim seems much harder to defend than does tolerance of harmless forms of diversity and opposition to arbitrary discrimination.

Labels:

Donald Trump,

guns,

Politics

Location:

North Bethesda, MD, USA

Thursday, May 19, 2016

Trump, China, and the Paris Climate Agreement

In a May 17th interview with Reuters, the presumptive Republican presidential nominee known simply as "the Donald" had quite a bit to say about the landmark climate agreement reached this past December in Paris, and he was so wrong about so much that I felt I had to say something.

Consider first Trump’s claim that he intends to renegotiate the Paris agreement: “I will be looking at that very, very seriously, and at a minimum I will be renegotiating those agreements, at a minimum. And at a maximum I may do something else.” “Something else,” we can only assume, means withdrawing from the agreement entirely.

The problem is that Trump is unlikely to be able to do any of this. Given that the process involved getting representatives of nearly 200 nations together in one place and took two weeks (not to mention months of planning), he certainly would not be able to convince the parties to the agreement to renegotiate it, and as Chris Mooney and Juliet Eilperin brought out in a recent article for the Washington Post, there is also a good chance that he would not be able to pull out of the agreement. This is so for two reasons: first, many countries--including the US and China--are currently making a concerted effort to ensure that the agreement goes into effect before President Obama leaves office next January, and second, no nation can pull out until at least three years after it goes into effect, and any withdrawals made then will take a year to go into effect.

Unfortunately, Mooney and Eilperin also make clear, the agreement is weak enough that by itself the fact that the next president may well be unable to withdraw hardly guarantees that the US under a President Trump would take meaningful climate action. Even if bound by the Paris agreement as it stands, a President Trump could (among other things) still nix President Obama’s Clean Power Plan, a crucial part of the US’s emissions reduction strategy. He could also abandon attempts to secure funding for the Green Climate Fund, an international mechanism meant to help poor countries reduce their emissions and take steps to protect themselves from the myriad adverse effects of climate change. Mooney and Eilperin suggest that, aside from international censure, this sort of thing would not result in any penalties for a Trump administration.

|

| Photo credit: Gage Skidmore |

Also noteworthy are Trump’s claims that the agreement is “one-sided” and that he does not believe China will adhere to the emissions reduction pledge it made ahead of Paris (its so-called Intended Nationally Determined Contribution or INDC). The implication here is clearly that China is not pulling its weight.

There are several problems with these claims.

First, it is not clear what if any reason there is supposed to be to doubt that China will fulfill its pledge to the international community. According to this analysis, China is on track to meet the goals set out in its INDC. And as Joe Romm over at Climate Progress was quick to point out, China in fact appears to be ahead of the game, with its emissions now apparently having plateaued a full fifteen years ahead of schedule!

All of this is possible because, Trump’s indication to the contrary notwithstanding, China is actually doing a ton to fight climate change. To mention just a few things the country is up to, China

- Plans to launch a nationwide cap and trade program in 2017 (source);

- Is rapidly expanding nuclear power generation capacity (source);

- Is expected to derive 50% of its electricity from renewable sources by 2030 (source);

- Aims to decrease coal consumption by 160 million tonnes in the next five years (source); and

- Is currently constructing a nationwide network of high-voltage, direct current power lines (source), a move that, the authors of this study found, would allow the US to reduce its emissions to 80% below 1990 levels if implemented here.

And as for whether or not China is pulling its weight, a couple of points are worth making.

First, the Climate Action Tracker, “an independent scientific analysis produced by four research organisations tracking climate action and global efforts towards the globally agreed aim of holding warming below 2°C,” ranks China ahead of the US on climate action! (See the chart on the left on this page.) I argued as much myself here.

Moreover, if any country is not pulling its weight, it is the US. For one thing, the US’s INDC is much less ambitious than it ought to be, as I argued here. And to make matters worse, one recent analysis found that currently the US is not even on track to achieve the relatively modest emissions reduction goals laid out in its INDC!

Together with his long history of climate change denial, the utter obliviousness to all this Trump displayed in this interview with Reuters suggests suggest that a Trump presidency would be very bad news for the climate. But hey--at least he’s not as bad as hemorrhoids!

UPDATE (5/27/16): Yesterday Trump made a speech about energy and the environment, and it was even worse than I had expected. He made clear his intentions not just to back out of the Paris agreement--which, as I've indicated, he may well be unable to do--abut also to do two terrible things that--I also said--he actually could do and that I expressed concern about: nix the Clean Power Plan and end adaptation funding for vulnerable communities across the globe. And as if this weren't enough, he also espoused a whole bunch of other really bad ideas I won't bother to get into. If you're interested, you can read more about it and watch the whole thing here.

I might also mention that, while doing research for this related blog post, I came across this UN page showing progress toward ratification of the Paris agreement. If you're as worried about what might happen with US climate policy if Trump becomes president as I am, you'll find this helpful.

First, the Climate Action Tracker, “an independent scientific analysis produced by four research organisations tracking climate action and global efforts towards the globally agreed aim of holding warming below 2°C,” ranks China ahead of the US on climate action! (See the chart on the left on this page.) I argued as much myself here.

Moreover, if any country is not pulling its weight, it is the US. For one thing, the US’s INDC is much less ambitious than it ought to be, as I argued here. And to make matters worse, one recent analysis found that currently the US is not even on track to achieve the relatively modest emissions reduction goals laid out in its INDC!

Together with his long history of climate change denial, the utter obliviousness to all this Trump displayed in this interview with Reuters suggests suggest that a Trump presidency would be very bad news for the climate. But hey--at least he’s not as bad as hemorrhoids!

UPDATE (5/27/16): Yesterday Trump made a speech about energy and the environment, and it was even worse than I had expected. He made clear his intentions not just to back out of the Paris agreement--which, as I've indicated, he may well be unable to do--abut also to do two terrible things that--I also said--he actually could do and that I expressed concern about: nix the Clean Power Plan and end adaptation funding for vulnerable communities across the globe. And as if this weren't enough, he also espoused a whole bunch of other really bad ideas I won't bother to get into. If you're interested, you can read more about it and watch the whole thing here.

I might also mention that, while doing research for this related blog post, I came across this UN page showing progress toward ratification of the Paris agreement. If you're as worried about what might happen with US climate policy if Trump becomes president as I am, you'll find this helpful.

Labels:

Climate Change,

Donald Trump,

Politics

Location:

North Bethesda, MD, USA

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)