I am a bit unusual among folks on the left insofar as I actually have a lot of personal experience with guns. Though I haven't done it since I was a teenager, I grew up hunting doves, squirrels, and deer with my grandpa; I think I killed my first deer when I was 11 or 12. That experience has led me to think a lot of things folks say about gun regulation is misguided. The push to outlaw assault weapons, for example, has long struck me as driven by an ignorant aversion to something that looks scary on the part of people who don't actually know anything about the relevant weapons. Generally speaking, so-called "assault weapons" are not different from semi-automatic weapons generally in ways that anyone should care about, at least as far as I know (happy to be corrected on this point). Other proposed measures, like outlawing high-capacity magazines, seem to me to go in the right direction but not nearly far enough.

For my part, I favor outlawing semi-automatic weapons, which make it much easier to kill more people in a given period of time and were used in both of the two worst mass shootings in the US in the last fifty years--in Orlando and Las Vegas.

So far as I can see, there is no good reason private citizens should be able to own these weapons. You certainly don't need them for hunting. If you need more than one shot to kill an animal, what you're doing is inhumane, and you should quit hunting, go to the range, and work on your shooting until you can hunt humanely. If the concern is self-defense, I fail to see why a shotgun used at close range isn't the most effective choice anyway. And if the idea is that we need guns so that we can form militias and, in that way, protect ourselves from government overreach--well, I think anyone who thinks that this is possible with semi-automatic weapons but not without is seriously underestimating the power of the US military. And besides, it seems to me clear that the public health benefits of a ban on semi-automatic weapons obviously outweigh whatever vanishingly small chance there is that a private militia with semi-automatic weapons would be more likely to succeed in its attempts to resist government overreach than one without. Honestly, the only reason I can think of to oppose such a ban is the irrational attachment to negative liberty that infects our public discourse generally.

However, there is good reason to go in for such a ban. There's robust evidence that regulations like this reduce gun-related deaths, and it's not hard to see why. Even if a ban didn't make it impossible to get hold of these, it would make doing so harder. It would accordingly keep many people from getting hold of these more lethal weapons, and that by itself would significantly reduce the number of deaths, even if mass shootings and other forms of gun violence still took place.

It's not clear whether or not banning these weapons would require revising the second amendment. (This piece, at least, suggests that it wouldn't.) If it would, though, I say so much the worse for the amendment.

Friday, October 6, 2017

Sunday, September 24, 2017

Some Very Rough Numbers on a Green New Deal

A couple

of recent developments got me thinking again about the possibility of a green

new deal.

The

first was the “Marshall

Plan for the United States” developed by the Center for American

Progress (CAP). Observing that wages are lower and unemployment is higher among

Americans without college degrees, they propose a jobs guarantee aimed at

putting these Americans back to work at well-paying jobs in education,

healthcare, and various forms of care work. For, they note,

There are not nearly enough home care workers

to aid the aged and disabled. Many working families with children under the age

of 5 need access to affordable child care. Schools need teachers’ aides, and

cities need EMTs.

They suggest, too,

that in addition to jobs, the government ought to fund infrastructure projects and apprenticeship programs

to train people for jobs for which they are not currently qualified.

The other was the

Democrats’ “Better Deal” initiative, which also

advocates job training and infrastructure investment.

All of this seems

great. A jobs guarantee empowers labor by reducing the power of the sack, and

because, on the CAP plan, these jobs would be relatively well-paid at $15/hour or

$36,000/year after Medicare and Social Security taxes, they would have the

welcome effect of putting upward pressure on wages throughout the economy. Moreover,

jobs like these that help us to sustain and improve our lives are precisely the

sorts of jobs we need more of as we seek to build a low-carbon economy.

The reason all this

got me thinking about a green new deal is that, their appeal notwithstanding, these

plans leave out a kind of work that is absolutely crucial to building a better

world: the construction and maintenance of green infrastructure, including not

just grid improvements and solar panel and wind turbine construction but also

the infrastructure necessary to expand opportunities for low-carbon leisure. Not

only is this work necessary; it is very well-suited for exactly the population

the CAP analysis is concerned with: you don’t need a college degree to do construction

work or to be a solar panel or wind turbine technician, though the latter do

require some training.

Maybe the reason for

this omission is that we can only fund so many jobs and so have to choose which

types of jobs to fund. But it is hardly obvious that green jobs are less

important than the kinds of jobs on which the CAP proposal focuses, and

besides, we may not have to choose: care work and educational jobs could be

funded from one source, green jobs from another. In particular, green jobs

might be funded using the revenue generated by a carbon tax and the $20.5 billion we currently spend every year subsidizing the

fossil fuel industry.

Senators Whitehouse

and Schatz recently proposed a carbon tax that would generate $2 trillion in

revenue over 10 years (details here), and

that proposal seems to be gaining some traction. Like many such proposals,

theirs is revenue-neutral, meaning that the revenue from this tax supplants

revenue that would otherwise have been collected by other means, such as the

corporate income tax. But a carbon tax needn’t be revenue-neutral. A carbon tax

might be structured in such a way that the revenue it generates does not

supplant but supplements other sources of revenue, and we might use that new

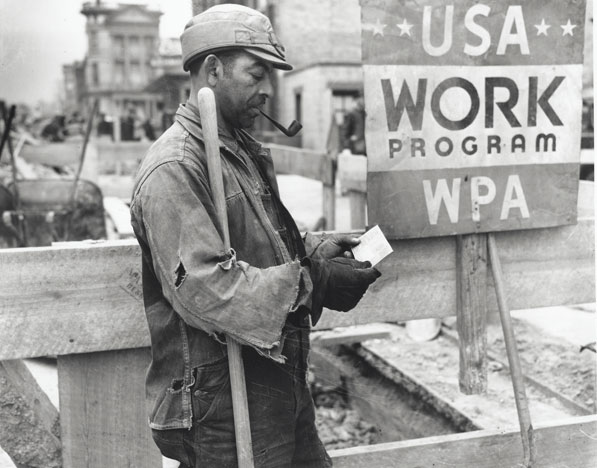

revenue to fund a WPA-style green jobs and

infrastructure program.

|

| A WPA worker receives a paycheck, January 1939. Source: National Archives. |

Now, as is

well-known, carbon taxes are regressive, so some of the revenue from the tax

would need to be used to offset price spikes for lower-income people.

Fortunately, this might be accomplished using only a small portion of the

revenue generated. Estimates as to how much of the revenue generated would be

necessary for this purpose appear to range from 10-25% (details here). Just to be safe,

we can be conservative in our estimates here and go with the highest estimates.

This would still leave 75% of the annual proceeds for other things.

Now it is worth

saying that even this number may be too high. We might also want to reserve

some of the revenue collected via a carbon tax to seed a rainy day fund for

Americans forced to relocate as a result of climate change and for others

adversely affected thereby. But even if we used another 25% of the revenue

collected for that purpose, we would still collect about $100 billion per year

for 10 years. Using the numbers in the CAP proposal as a guide, that should be

enough to fund about 2.8 million jobs at an after-tax wage of $15/hr. Were we

to also use the $20.5 billion/year we currently spend in fossil fuel subsidies

for this purpose, we could create about 570,000 more such jobs, making for a

total of 3.37 million jobs. And

remember, that’s using the most conservative figures around to make sure that

tax isn’t regressive and using an enormous amount of money to help people

adversely affected by climate change.

This is, of course,

a highly ambitious proposal, one unlikely to get anywhere in the current

political climate. Nevertheless it deserves serious consideration for several

reasons. Not only is it exactly the kind of bold vision needed to correct the impression that the Democratic

Party doesn’t stand for anything. Not only does it have the same advantages as

the CAP proposal with respect to the empowerment of labor and economy-wide

upward pressure on wages. In addition to all this, it has a distinct advantage

over many other carbon tax proposals. Even if this is not exactly the aim, the

likely if not inevitable effect of instituting a carbon tax high enough to

ensure that the prices of fossil fuels reflect their true cost to society is to

end our reliance on such fuels. It is for that reason a bad idea to use the

revenues generated thereby to fund anything we expect to continue to need funds

after we are no longer using carbon-intensive fuels: otherwise, we set

ourselves up for funding shortfalls in the future. The advantage of using

revenues from a carbon tax to fund a WPA-style green jobs program is that many

such jobs will become unnecessary around the same time we stop using fossil

fuels, and not just coincidentally. For these are precisely the jobs that bring

into existence the infrastructure we need in order to wean ourselves off of

gas, oil, and coal. As soon as they’re done, there will be nothing left to tax.

Notably, this aspect

of the proposal also gives to it something of a poetic character: for the

proposal is, in effect, to build the new world on the back of the old.

Thursday, March 2, 2017

In Defense of Safety Nets

With the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and much of the rest of America's already-inadequate safety net on the chopping block, it seemed to me fitting to write a short defense of safety nets, one that emphasizes the moral and philosophical position underlying my view here rather than getting lost in the weeds, as so many discussions of safety net programs seem to.

My view here is grounded in the one of the oldest and most widely accepted moral views, the so-called Golden Rule: we ought to do to others as we would prefer that they do to us were our circumstances relevantly similar to theirs. It is also grounded in the view that one of the government's most basic functions is to protect its citizens from danger, one form of which is the vicissitudes of fortune (illness, unexpected expenses, damage to or loss of property, etc.). Both these thoughts are captured nicely by the following thought experiment, developed by the American political philosopher John Rawls in the early '70s.

Try to imagine that you are in a situation where you don't know anything about what kind of person you are and are trying to imagine what a country should be like. So: you don't know if you're a man or a woman; what color your skin is; if you're able-bodied; if you're Christian, Muslim, non-religious, Jewish, or something else; if you're gay, bisexual,or straight; if you're cis- or transgender; if you're poor or rich or somewhere in between; if you have a family and friends you can rely or in hard times or if you don't; and so on. In short, all you know is that you live in some country. Now consider: if that were your situation, and if you could decide what the country you lived in would be like, how would you want it to be?

I don't think that's right or fair; in my view a society cannot call itself decent if it is willing to take the chance that people it might have helped die on the street. I accordingly think the government should be willing to extend a hand to anyone who needs it--to give them food to eat, a roof over their heads, and clothes to wear, whatever their color, creed, sexual orientation, etc. That way, even if I don't know anything about myself other than that I'm a citizen or perhaps even just a resident, I know that, if I'm in trouble, I can count on someone offering it to me, whatever else might turn out to be true about me. I don't just have to hope that someone might have decided to start a charity or a church that will be willing to help me: I can count on it.

The fundamental point underlying all this is a simple moral one. The vicissitudes of fortune are a kind of danger that haunts even those of us who manage to escape its cruelest blows. And sometimes, when disaster does strike, people end up in situations with which they can't or don't know how to cope--often through no fault of their own. In those moments people need a helping hand. Being a decent society means recognizing this and doing what we can to help those who fall on hard times, not turning our backs on the needy to punish the takers, all the while singing paeans to liberty and caught up in absurd, Randian fever dreams about self-made men. The hard truth is that none of us knows when we might need a hand; decency demands that we be willing to offer ours.

My view here is grounded in the one of the oldest and most widely accepted moral views, the so-called Golden Rule: we ought to do to others as we would prefer that they do to us were our circumstances relevantly similar to theirs. It is also grounded in the view that one of the government's most basic functions is to protect its citizens from danger, one form of which is the vicissitudes of fortune (illness, unexpected expenses, damage to or loss of property, etc.). Both these thoughts are captured nicely by the following thought experiment, developed by the American political philosopher John Rawls in the early '70s.

Try to imagine that you are in a situation where you don't know anything about what kind of person you are and are trying to imagine what a country should be like. So: you don't know if you're a man or a woman; what color your skin is; if you're able-bodied; if you're Christian, Muslim, non-religious, Jewish, or something else; if you're gay, bisexual,or straight; if you're cis- or transgender; if you're poor or rich or somewhere in between; if you have a family and friends you can rely or in hard times or if you don't; and so on. In short, all you know is that you live in some country. Now consider: if that were your situation, and if you could decide what the country you lived in would be like, how would you want it to be?

In particular, what kinds of resources would you like to have available to you if you fell on hard times? For example, would you want it to be the case that, if you needed help, the only place to turn would be the church and charities? Remember: because these are private organizations run by private citizens, there is no guarantee there will be any of them at all and, if there are, no guarantee that there will be enough of them or that they will be able to provide the help you need. Moreover, even if there are enough and they can help, they might not. Maybe you're gay and they don't like gay people. Maybe you're black and they don't like black folks. Maybe you're Jewish and they don't like Jews. And so on.

I don't think that's right or fair; in my view a society cannot call itself decent if it is willing to take the chance that people it might have helped die on the street. I accordingly think the government should be willing to extend a hand to anyone who needs it--to give them food to eat, a roof over their heads, and clothes to wear, whatever their color, creed, sexual orientation, etc. That way, even if I don't know anything about myself other than that I'm a citizen or perhaps even just a resident, I know that, if I'm in trouble, I can count on someone offering it to me, whatever else might turn out to be true about me. I don't just have to hope that someone might have decided to start a charity or a church that will be willing to help me: I can count on it.

A lot people have concerns about the kinds of government programs I'm advocating, and it would be impossible to address all of them without making this far too long. So I just want touch at least briefly on those I hear most often.

Perhaps the concern about safety net programs I hear expressed most frequently is that they enable free riders or moochers by giving them something for nothing. I think the fundamental thought behind this objection is that our society should be such that, the harder a person works and the higher the quality of their work, the better they do. Safety nets irritate people who press this objection because, they think, they stand in the way of the realization of this ideal by rewarding laziness. This strikes them as unfair to people who are willing to do their part.

In principle, I

don't see anything wrong with this meritocratic ideal. In general, it seems to

me a good thing to reward people for working hard at helpful tasks. Nevertheless I think this is a very bad objection to safety nets for a couple of reasons.

First, I just do not think our society is anywhere close to being meritocratic in this sense. On the one hand, people born into rich or powerful families often do quite well for themselves despite not being especially capable. Sometimes this is because their families have connections and influence that enable them to do things they wouldn't otherwise be able to; for example, this appear to be what explains the admission to Harvard of Jared Kushner, Donald Trump's son-in-law and according to his high-school teachers a "less than stellar" student (details here). Other times it is just because such people come into the world with a kind of support system or fail-safe people born into less fortunate circumstances do not: if they ever end up in a tight spot, they can rely on their family's wealth and connections to get them out of it. On the other, our society often throws up arbitrary barriers to advancement that make it much harder for some people to do well for themselves in the first place. These obstacles often take the form of class-, race-, gender-, sexual orientation-, or gender identity-based prejudice and structural barriers. I support safety nets in part because I think they go some way toward rectifying that defect by removing these arbitrary obstacles to advancement by making available to everyone the kind of support system only the rich would otherwise have.

But--second--even if our society were perfectly meritocratic--even if everybody's level of well-being were perfectly correlated with how talented or capable they are and how hard they are willing to work--we would still need a robust safety net. For the mere fact that someone is not particularly capable or useful should not mean that they lose their house, that they die because they can't afford healthcare, or that they go hungry. We should not punish those with mental illness or with physical or mental disabilities for being the way they are; instead, recognizing our common humanity and the vulnerability that is a basic fact of all our lives, we should take care of them. The opposite view is just callous indifference.

Someone might grant me all this but still worry that people who don't really need them will take advantage of these programs. Again I agree that it is a bad thing for people to be lazy and take advantage of programs intended to help people get back on their feet: the public coffers are not bottomless, so we would do well not to waste money on people who don't really need it. But this belief leads me to different conclusions than it does those who press this objection because I care more about ensuring that people do not go hungry, end up homeless, lose limbs from untreated diabetes, etc. than I do about the possibility that someone might take advantage of safety net programs. For this reason, my response to learning that people are taking advantage of safety net programs is to think that, if anything, we need to alter the programs they’re taking advantage of to make it harder and less appealing for them to do that, not abolish the programs. But even this, it bears saying, is a dangerous path. For once we start down it, there is a tendency to increase the number of hoops people have to jump through in order to benefit from the program in question. Not only does this increase the likelihood that people who need those benefits won't get them--a possibility that, to my mind, is far worse than some getting them even though they don't need them--it also often increases the cost of the program. That in turn may decrease public support for it and lead, in time, to its elimination. So there are sometimes significant costs to implementing measures designed to restrict access to safety net programs, dangers anyone attempting to eliminate free riders would do well to keep in mind. Though not ideal, it is far better for someone to get a benefit they don't need than for them to need a benefit they can't get.

Another common objection to safety net programs is that, although it is certainly a good thing to feed the hungry, house the homeless, tend the sick, and so on, the associated costs to our liberty far outweigh the benefits of governmental programs designed to do this. This is the objection to the ACA I've heard more often than any other: people hate being coerced into buying healthcare. Against this, however, two points. First, liberty is without a doubt a valuable thing, but this objection suggests a perverse fetishization of liberty, a blind zeal for non-interference that fails to distinguish those freedoms that are worth caring about from those that are not. For supposing that we are talking about offering these programs in a relatively wealthy society and financing them primarily by taxing its wealthiest citizens--as we undeniably are in the United States--the freedom in question is that of people who have more than they need to hoard their wealth and deny to those who lack it the minimum necessary for a decent life. I cannot see a society that values that particularly liberty over meeting people's basic needs as anything but cruel and selfish. Moreover, it must be said that that safety net programs that ensure that all people have access to housing, enough food and clothing, and healthcare are themselves in an important sense liberating: by putting in place a kind of ground floor below which people are not allowed to fall, they insulate people from the whims of fate and, in that way, go some way toward liberating them from oppressive forces to which all of us are subject to at least some extent.

First, I just do not think our society is anywhere close to being meritocratic in this sense. On the one hand, people born into rich or powerful families often do quite well for themselves despite not being especially capable. Sometimes this is because their families have connections and influence that enable them to do things they wouldn't otherwise be able to; for example, this appear to be what explains the admission to Harvard of Jared Kushner, Donald Trump's son-in-law and according to his high-school teachers a "less than stellar" student (details here). Other times it is just because such people come into the world with a kind of support system or fail-safe people born into less fortunate circumstances do not: if they ever end up in a tight spot, they can rely on their family's wealth and connections to get them out of it. On the other, our society often throws up arbitrary barriers to advancement that make it much harder for some people to do well for themselves in the first place. These obstacles often take the form of class-, race-, gender-, sexual orientation-, or gender identity-based prejudice and structural barriers. I support safety nets in part because I think they go some way toward rectifying that defect by removing these arbitrary obstacles to advancement by making available to everyone the kind of support system only the rich would otherwise have.

But--second--even if our society were perfectly meritocratic--even if everybody's level of well-being were perfectly correlated with how talented or capable they are and how hard they are willing to work--we would still need a robust safety net. For the mere fact that someone is not particularly capable or useful should not mean that they lose their house, that they die because they can't afford healthcare, or that they go hungry. We should not punish those with mental illness or with physical or mental disabilities for being the way they are; instead, recognizing our common humanity and the vulnerability that is a basic fact of all our lives, we should take care of them. The opposite view is just callous indifference.

Someone might grant me all this but still worry that people who don't really need them will take advantage of these programs. Again I agree that it is a bad thing for people to be lazy and take advantage of programs intended to help people get back on their feet: the public coffers are not bottomless, so we would do well not to waste money on people who don't really need it. But this belief leads me to different conclusions than it does those who press this objection because I care more about ensuring that people do not go hungry, end up homeless, lose limbs from untreated diabetes, etc. than I do about the possibility that someone might take advantage of safety net programs. For this reason, my response to learning that people are taking advantage of safety net programs is to think that, if anything, we need to alter the programs they’re taking advantage of to make it harder and less appealing for them to do that, not abolish the programs. But even this, it bears saying, is a dangerous path. For once we start down it, there is a tendency to increase the number of hoops people have to jump through in order to benefit from the program in question. Not only does this increase the likelihood that people who need those benefits won't get them--a possibility that, to my mind, is far worse than some getting them even though they don't need them--it also often increases the cost of the program. That in turn may decrease public support for it and lead, in time, to its elimination. So there are sometimes significant costs to implementing measures designed to restrict access to safety net programs, dangers anyone attempting to eliminate free riders would do well to keep in mind. Though not ideal, it is far better for someone to get a benefit they don't need than for them to need a benefit they can't get.

Another common objection to safety net programs is that, although it is certainly a good thing to feed the hungry, house the homeless, tend the sick, and so on, the associated costs to our liberty far outweigh the benefits of governmental programs designed to do this. This is the objection to the ACA I've heard more often than any other: people hate being coerced into buying healthcare. Against this, however, two points. First, liberty is without a doubt a valuable thing, but this objection suggests a perverse fetishization of liberty, a blind zeal for non-interference that fails to distinguish those freedoms that are worth caring about from those that are not. For supposing that we are talking about offering these programs in a relatively wealthy society and financing them primarily by taxing its wealthiest citizens--as we undeniably are in the United States--the freedom in question is that of people who have more than they need to hoard their wealth and deny to those who lack it the minimum necessary for a decent life. I cannot see a society that values that particularly liberty over meeting people's basic needs as anything but cruel and selfish. Moreover, it must be said that that safety net programs that ensure that all people have access to housing, enough food and clothing, and healthcare are themselves in an important sense liberating: by putting in place a kind of ground floor below which people are not allowed to fall, they insulate people from the whims of fate and, in that way, go some way toward liberating them from oppressive forces to which all of us are subject to at least some extent.

The fundamental point underlying all this is a simple moral one. The vicissitudes of fortune are a kind of danger that haunts even those of us who manage to escape its cruelest blows. And sometimes, when disaster does strike, people end up in situations with which they can't or don't know how to cope--often through no fault of their own. In those moments people need a helping hand. Being a decent society means recognizing this and doing what we can to help those who fall on hard times, not turning our backs on the needy to punish the takers, all the while singing paeans to liberty and caught up in absurd, Randian fever dreams about self-made men. The hard truth is that none of us knows when we might need a hand; decency demands that we be willing to offer ours.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)