A couple

of recent developments got me thinking again about the possibility of a green

new deal.

The

first was the “Marshall

Plan for the United States” developed by the Center for American

Progress (CAP). Observing that wages are lower and unemployment is higher among

Americans without college degrees, they propose a jobs guarantee aimed at

putting these Americans back to work at well-paying jobs in education,

healthcare, and various forms of care work. For, they note,

There are not nearly enough home care workers

to aid the aged and disabled. Many working families with children under the age

of 5 need access to affordable child care. Schools need teachers’ aides, and

cities need EMTs.

They suggest, too,

that in addition to jobs, the government ought to fund infrastructure projects and apprenticeship programs

to train people for jobs for which they are not currently qualified.

The other was the

Democrats’ “Better Deal” initiative, which also

advocates job training and infrastructure investment.

All of this seems

great. A jobs guarantee empowers labor by reducing the power of the sack, and

because, on the CAP plan, these jobs would be relatively well-paid at $15/hour or

$36,000/year after Medicare and Social Security taxes, they would have the

welcome effect of putting upward pressure on wages throughout the economy. Moreover,

jobs like these that help us to sustain and improve our lives are precisely the

sorts of jobs we need more of as we seek to build a low-carbon economy.

The reason all this

got me thinking about a green new deal is that, their appeal notwithstanding, these

plans leave out a kind of work that is absolutely crucial to building a better

world: the construction and maintenance of green infrastructure, including not

just grid improvements and solar panel and wind turbine construction but also

the infrastructure necessary to expand opportunities for low-carbon leisure. Not

only is this work necessary; it is very well-suited for exactly the population

the CAP analysis is concerned with: you don’t need a college degree to do construction

work or to be a solar panel or wind turbine technician, though the latter do

require some training.

Maybe the reason for

this omission is that we can only fund so many jobs and so have to choose which

types of jobs to fund. But it is hardly obvious that green jobs are less

important than the kinds of jobs on which the CAP proposal focuses, and

besides, we may not have to choose: care work and educational jobs could be

funded from one source, green jobs from another. In particular, green jobs

might be funded using the revenue generated by a carbon tax and the $20.5 billion we currently spend every year subsidizing the

fossil fuel industry.

Senators Whitehouse

and Schatz recently proposed a carbon tax that would generate $2 trillion in

revenue over 10 years (details here), and

that proposal seems to be gaining some traction. Like many such proposals,

theirs is revenue-neutral, meaning that the revenue from this tax supplants

revenue that would otherwise have been collected by other means, such as the

corporate income tax. But a carbon tax needn’t be revenue-neutral. A carbon tax

might be structured in such a way that the revenue it generates does not

supplant but supplements other sources of revenue, and we might use that new

revenue to fund a WPA-style green jobs and

infrastructure program.

|

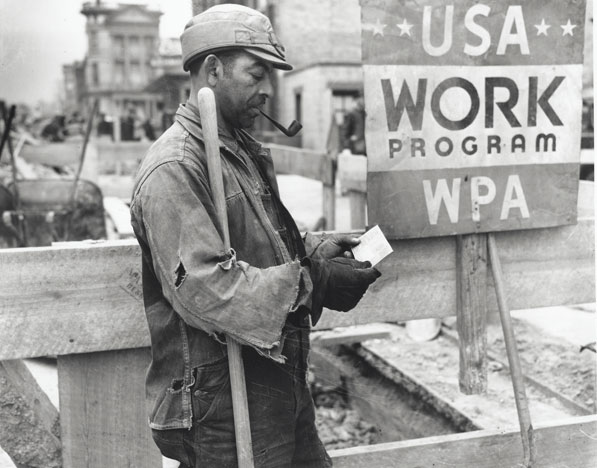

| A WPA worker receives a paycheck, January 1939. Source: National Archives. |

Now, as is

well-known, carbon taxes are regressive, so some of the revenue from the tax

would need to be used to offset price spikes for lower-income people.

Fortunately, this might be accomplished using only a small portion of the

revenue generated. Estimates as to how much of the revenue generated would be

necessary for this purpose appear to range from 10-25% (details here). Just to be safe,

we can be conservative in our estimates here and go with the highest estimates.

This would still leave 75% of the annual proceeds for other things.

Now it is worth

saying that even this number may be too high. We might also want to reserve

some of the revenue collected via a carbon tax to seed a rainy day fund for

Americans forced to relocate as a result of climate change and for others

adversely affected thereby. But even if we used another 25% of the revenue

collected for that purpose, we would still collect about $100 billion per year

for 10 years. Using the numbers in the CAP proposal as a guide, that should be

enough to fund about 2.8 million jobs at an after-tax wage of $15/hr. Were we

to also use the $20.5 billion/year we currently spend in fossil fuel subsidies

for this purpose, we could create about 570,000 more such jobs, making for a

total of 3.37 million jobs. And

remember, that’s using the most conservative figures around to make sure that

tax isn’t regressive and using an enormous amount of money to help people

adversely affected by climate change.

This is, of course,

a highly ambitious proposal, one unlikely to get anywhere in the current

political climate. Nevertheless it deserves serious consideration for several

reasons. Not only is it exactly the kind of bold vision needed to correct the impression that the Democratic

Party doesn’t stand for anything. Not only does it have the same advantages as

the CAP proposal with respect to the empowerment of labor and economy-wide

upward pressure on wages. In addition to all this, it has a distinct advantage

over many other carbon tax proposals. Even if this is not exactly the aim, the

likely if not inevitable effect of instituting a carbon tax high enough to

ensure that the prices of fossil fuels reflect their true cost to society is to

end our reliance on such fuels. It is for that reason a bad idea to use the

revenues generated thereby to fund anything we expect to continue to need funds

after we are no longer using carbon-intensive fuels: otherwise, we set

ourselves up for funding shortfalls in the future. The advantage of using

revenues from a carbon tax to fund a WPA-style green jobs program is that many

such jobs will become unnecessary around the same time we stop using fossil

fuels, and not just coincidentally. For these are precisely the jobs that bring

into existence the infrastructure we need in order to wean ourselves off of

gas, oil, and coal. As soon as they’re done, there will be nothing left to tax.

Notably, this aspect

of the proposal also gives to it something of a poetic character: for the

proposal is, in effect, to build the new world on the back of the old.